As public debate heats up over whether the United States should create a central bank digital currency (CBDC), there is another option that deserves consideration: Treasury Accounts. The Treasury Department could, relatively quickly, create digital accounts to provide payment services that would be especially valuable to unbanked and underbanked individuals. These accounts might not possess all the technological advances of a full-blown CBDC, but they would be much easier to establish and could be implemented now under existing statutory authority. Importantly, Treasury Accounts could immediately improve access to financial services for the millions of Americans who have limited access to banking services today and also greatly facilitate the distribution of federal benefit programs to all Americans. Treasury Accounts are not an alternative to CBDCs but rather a faster, easier way to achieve some of the primary objectives of those who favor creating a CBDC. The creation of Treasury Accounts would represent a concrete step forward in the Treasury Department’s efforts “to unlock the unrealized potential of underserved communities,” an initiative the Department announced in connection with Secretary Yellen’s appointment of the Department’s first counselor for racial equity last Fall.

Many believe a CBDC can be a means to expand financial inclusion. One prominent proposal known as Fed Accounts—which has attracted support from progressive members of Congress–would create a system of retail accounts at the Federal Reserve that would provide all Americans with the opportunity to have a bank account at no cost. These accounts could also be used to distribute federal benefits on an expedited basis. But many believe that direct Federal Reserve accounts for individuals would be an inappropriate expansion of the Federal Reserve’s role, and that in any event the Federal Reserve would not be well equipped to reach the kinds of retail customers that do not have traditional bank accounts. Moreover, the creation of a CBDC in the United States faces many challenges, both technical and political. There is substantial debate not only as to how such an instrument should be designed, but whether it is even needed. Almost certainly it will take a number of years before a consensus emerges on the proper path forward.

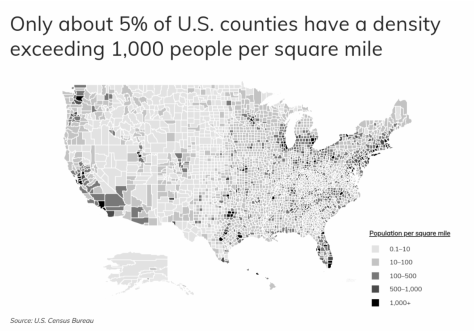

The financial inclusion need remains significant and urgent, however. According to the FDIC, 5.4% of American households are unbanked and roughly three times as many more underbanked—the latter term meaning those who have a bank account but use expensive nonbank services like check cashing, money orders, payday lenders and international remittance services. The unbanked as a percentage of the population is greater in the United States than in all other G7 countries and far more concentrated among those at the lower end of the income distribution. Despite considerable efforts from consumer advocates over decades, neither regulatory authorities nor private initiatives have succeeded in providing universal access to financial services.

The Treasury Department, in our view, is a much more logical place for the federal government to experiment with improving access to financial services. It has decades of experience as well as the legal authority to create a program of Treasury Accounts that could reach the underserved. During the Pandemic, it was the Treasury Department along with the Internal Revenue Service, which is a bureau within the Department, that was charged with distributing emergency payments and later advanced Child Tax Credits to millions of households, including many without traditional bank accounts. While the process was bumpy at times, the Department’s overall performance in distributing almost $1 trillion in Pandemic benefits in over half a billion separate payments was impressive. The Treasury has also devised multiple programs over the years designed to reach the underserved. This includes programs to distribute federal benefits which in some cases incorporated payment services. The Treasury created the Direct Express program which enables unbanked individuals to receive federal benefits on a privately-managed pre-paid card. It also developed the digital Treasury Direct interface that allows individuals to invest directly in government securities, and it has experimented with the creation of a new class of digital savings bonds designed to encourage retirement savings.

Our proposal for Treasury Accounts would provide low cost, no-frills payment services and encourage the accumulation of emergency savings reserves. The breadth of the eligibility criteria would need to be determined, but they would be designed to meet the needs of low-income individuals and particularly the unbanked and underbanked, leveraging the experiences that the Department has gained working with fintech firms and non-profit groups during the Pandemic. For example, Treasury Accounts could provide:

- basic services and fees incorporating recent Fintech approaches built on streamlined mobile banking interfaces and checkless payments as well as no overdraft or non-sufficient funds fees and very low or no balance requirements and monthly maintenance fees.

- faster clearing of deposited checks compared to private market offerings, a critical need for people who live paycheck to paycheck. The Treasury could provide for immediate clearing of government checks and facilitate direct deposit from participating employers.

- more efficient know-your-customer screening, which often prevents or discourages unbanked persons from obtaining private accounts. The account opening screening could be considered largely or entirely satisfied by the fact that someone has already established eligibility for and is receiving government benefits; and

- a maximum balance to minimize disintermediation risk, with provisions for rolling over accounts that reach such limitations into private accounts.

The program could be implemented using Treasury’s financial agent authority to partner with commercial institutions, the cost of which is covered under a permanent, indefinite appropriation enacted in 2004. The financial agents would provide all customer-facing functions. These agents could include fintech firms that could provide innovative forms of outreach, including through mobile applications, as well as minority-owned and other firms that have experience reaching underserved populations. We describe two possible legal structures for creating Treasury Accounts that would not require new legislation, one building on the existing Direct Express program, and the other utilizing Treasury’s savings bond authority. We conclude by discussing how Treasury Accounts compare to a CBDC as a vehicle to promote financial access, and how they could generate useful information and insights that might later be incorporated into any CBDC that the nation eventually decides to adopt.