For decades, labor cost differences have been a primary influence in the continuous shift of manufacturing production from the U.S. to China. In 1980, the cost of labor in the U.S. was more than 30 times of that in China. As China became less agrarian and more of its population migrated to large cities to work in new factories, wages rose dramatically. By 2018, the U.S.-China wage gap had closed to only four times, rising approximately 200% in the U.S. but over 2,000% in China over nearly 40 years. Yet, despite the sharp rise in Chinese manufacturing wages over the last 20 years, offshoring continued. The U.S. manufacturing industry suffered, including millions of lost jobs, stagnant inflation-adjusted wages and a decline of the middle class.

Change in wages in U.S. and China from 1980-2018

Predictable wage increases in China do not tell the whole story of America’s declining status as a factory for the world. The establishment of special, quasi-free market Special Economic Zones, seemingly endless supply of relatively inexpensive labor, and fully globalized shipping networks allowed China to capitalize on the high cost of manufacturing in the U.S., but perhaps a more important development was the world’s relentless march toward automation and robotics.

The replacement of manual labor by machines and software may have had just as much influence on the decline of the American manufacturing industry as foreign labor costs, domestic labor unions, and international trade policy. Whether attributable to man or machine, parts of the American manufacturing industry have struggled for decades to be competitive and relevant, leading the industry to focus the remaining competitive advantages on the manufacture of niche, value-add, or raw material-dependent products.

Despite a steady increase in their workers’ productivity, most American manufacturers have not been able to automate or reduce logistics costs enough to remain competitive—and offshoring, primarily to Asia, became an unfortunate reality for corporations of all sizes. When any company established a manufacturing presence in China and built a global supply chain, pressure was applied to its remaining competitors in the U.S. to either innovate or follow suit. Among some of the first U.S. manufacturers to offshore en masse were labor-intensive sectors, such as furniture and textiles, followed by manufacturers with relatively low transportation costs, such as pharmaceuticals and semiconductors.

Approximately a decade ago, several institutions in the U.S. converged on a theory that significant changes in U.S. manufacturers’ cost-benefit analysis were occurring and could create a tipping point toward reshoring certain products. The average hourly wages for reliable, competent labor in China and the cost of transporting manufactured goods safely and efficiently to consumers had shifted to such an extent that American manufacturers could potentially reshore their operations to the U.S. or near-shore them to Latin America. Their tipping point theory, predicated on higher Chinese production wages and increasingly complex and expensive global transportation and logistics costs, asserted that over a dozen manufacturing sectors showed formulaic probability of reshoring.

Today, nearly 10 years after the tipping point theory was first publicized, the American manufacturing industry may be on the precipice of another large surge in activity. Through the Great Recession and recovery, American manufacturing was kept buoyant by high-margin, low-volume products. Factoring in the current public health emergency and the current Administration’s response, the U.S. manufacturing sector could regain some of its prior job losses in impacted industries.

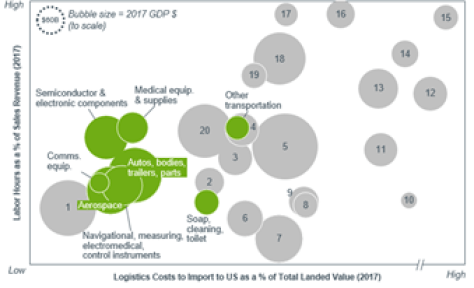

The U.S. manufacturing industry is at a unique and unprecedented crossroads. Of the dozen or so manufacturing sectors that previously showed potential for being reshored by rising labor costs and comparatively steep transportation and logistics costs, the tipping point has further shifted, and justification for domestic manufacturing appears stronger. As the world struggles to contain the coronavirus and understand its long-term implications on our social, medical, educational and economic systems, Duff & Phelps has created a new analysis of the prior tipping point theory and integrated several key strategic factors that carry more (or at least equal) weight in a post-COVID-19 world.

To refresh the study, Duff & Phelps adjusted for new global economic conditions, plotted current data for all major production categories and determined a new tipping point for sectors across the manufacturing industry. We began our analysis by identifying, measuring, and weighting key metrics for companies with manufacturing operations in China, including cost (labor + logistics), automation (labor productivity), innovation (R&D, IP, patents, etc.), quality and safety, sustainability (environmental regulations and pollution), and national security (critical/essential designations). Specifically, our “reshoring analysis” used six objective criteria to analyze 28 sectors of the American manufacturing industry, identified by North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) codes, which were ultimately ranked according to which showed the greatest potential for re-shoring

The following six criteria and circumstantial factors show the highest probability of a given sector to reshore:

Cost: sectors with low labor costs and high logistics costs

Level of Automation: sectors that have seen a major increase in labor productivity

Innovation and Intellectual Property: sectors with relatively high R&D spending, particularly valuable intellectual property embedded within the manufacturing process or significant patent applications

Product Quality and Safety: sectors with stricter quality and safety regulations (e.g., food, drugs)

Essential Business Designation: businesses, sectors or products officially designated as critical or essential by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security or other governmental authority

Environmental Regulations: sectors whose cost of capital justifies capital investment in real or personal property improvements that allow production to meet or exceed U.S. emissions or pollution regulations

In our analysis of the six primary criteria and 28 sectors, a composite of the eight highest-scoring production categories emerged as the most probable candidates to reshore to the U.S. They share the characteristics of relatively low labor and high transportation costs and feature some of the most advanced robotics, automation and manufacturing techniques across all technology-enabled industries. Their manufacturing processes are more compliant with and conducive to U.S. environmental regulations, labor laws, intellectual property protections and consumer safety standards. Their profit margins and global demand also tend to alleviate concerns associated with reshoring investment costs. Given the U.S. government’s renewed focus on homeland security and essential goods and services in the wake of COVID-19, the following industry sectors will have to reevaluate their manufacturing costs, supply chain reliability and risk of significant business interruption even while the pandemic is still ongoing:

-Automobiles, bodies, trailers and parts

-Other transportation equipment (e.g., boats, rail)

-Navigational, measuring, electromedical and control instruments

-Basic chemicals

-Semiconductor and electronic components

-Medical equipment and supplies

-Communications equipment

-Aerospace products and parts.

U.S.-China trade flows and top candidates for reshoring

Today, cost isn’t the only significant factor influencing U.S. corporations’ manufacturing footprint. Based on the following factors, manufacturing in the U.S. may become economically feasible for more sectors and the U.S. may experience active and passive reshoring effects as companies consider these variables:

Economic

-Rising cost of labor in China

-Increasing transparency into foreign working conditions and safety measures

-Rising logistics costs

-Corporate supply chain risk mitigation and the identification of critical supplies

-Internet/information-driven consumer awareness and sentiment

-Cost and threat of intellectual property theft

Environmental

-Enforcement of environmental laws and regulations in China’s manufacturing sector

-Sustainability and a global shift away from fossil-fuels power

-Reduced consumerism among millennials and younger generations with increased spending power for durable and non-durable goods

Geopolitical

-U.S.-China trade war and tariff impacts

-Anti-globalization and nationalist political, social and cultural trends across the world

-Consumers’ increasing demands for transparency of product content and origin

-The Trump administration’s calls for U.S. companies to reduce China-centric supply chains, even before COVID-19

-U.S.-China tensions over democracy protests in Hong Kong, origins of COVID-19, military escalation along the Indian border and in the South China Sea

-Human rights abuses of millions of ethnic Uyghurs in Chinese detention camps

Domestic Policy

-U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement ratification

-COVID-19 related essential business, industry and product designations by various U.S. agencies

-Potential for new legislation, regulation or designation of previously outsourced or offshored products and services that are now deemed critical to the U.S. economy or economic infrastructure

Regardless of COVID-19’s impact to the global economic structure, many large American manufacturing operations will likely remain anchored in China since production in the U.S. continues to be labor-intensive and/or global distribution is still so cost=efficient. However, our analysis suggests that additional factors beyond economic ones are being weighted more heavily and that many products historically made in China and destined for U.S. consumers or other markets around the world show high potential for being reshored.

__________________________________________________________________

Gregory Burkart is managing director and global leader of Duff & Phelps’ Site Selection and Incentives Advisory practice. Kurt Steltenpohl is a managing director in Duff & Phelps’ Transaction Advisory Services practice and leader of Operations Consulting.

Duff & Phelps’ Danielle Dipietra, Meegan Spicer, Anthony Schum and Wesley Michael also contributed to this article.

A version of this article was previously published in IndustryWeek.